https://gmt.io/?ref=3 Here you can make billlions of dollars!!! Cheaply its Johannes!!!

Economics (/ˌɛkəˈnɒmɪks, ˌiːkə-/)[1] is a social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.[2][3]

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes what's viewed as basic elements in the economy, including individual agents and markets, their interactions, and the outcomes of interactions. Individual agents may include, for example, households, firms, buyers, and sellers. Macroeconomics analyzes the economy as a system where production, consumption, saving, and investment interact, and factors affecting it: employment of the resources of labour, capital, and land, currency inflation, economic growth, and public policies that have impact on these elements.

Other broad distinctions within economics include those between positive economics, describing "what is", and normative economics, advocating "what ought to be";[4] between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioural economics; and between mainstream economics and heterodox economics.[5]

Economic analysis can be applied throughout society, including business,[6] finance, cybersecurity,[7] health care,[8] engineering[9] and government.[10] It is also applied to such diverse subjects as crime,[11] education,[12] the family,[13] feminism,[14] law,[15] philosophy,[16] politics, religion,[17] social institutions, war,[18] science,[19] and the environment.[20]

Definitions of economics over time

The earlier term for the discipline was 'political economy', but since the late 19th century, it has commonly been called 'economics'.[21] The term is ultimately derived from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomia) which is a term for the "way (nomos) to run a household (oikos)", or in other words the know-how of an οἰκονομικός (oikonomikos), or "household or homestead manager". Derived terms such as "economy" can therefore often mean "frugal" or "thrifty".[22][23][24][25] By extension then, "political economy" was the way to manage a polis or state.

There are a variety of modern definitions of economics; some reflect evolving views of the subject or different views among economists.[26][27] Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1776) defined what was then called political economy as "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations", in particular as:

Jean-Baptiste Say (1803), distinguishing the subject matter from its public-policy uses, defined it as the science of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.[29] On the satirical side, Thomas Carlyle (1849) coined "the dismal science" as an epithet for classical economics, in this context, commonly linked to the pessimistic analysis of Malthus (1798).[30] John Stuart Mill (1844) delimited the subject matter further:

Alfred Marshall provided a still widely cited definition in his textbook Principles of Economics (1890) that extended analysis beyond wealth and from the societal to the microeconomic level:

Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "[p]erhaps the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject":[27]

Robbins described the definition as not classificatory in "pick[ing] out certain kinds of behaviour" but rather analytical in "focus[ing] attention on a particular aspect of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of scarcity."[34] He affirmed that previous economists have usually centred their studies on the analysis of wealth: how wealth is created (production), distributed, and consumed; and how wealth can grow.[35] But he said that economics can be used to study other things, such as war, that are outside its usual focus. This is because war has as the goal winning it (as a sought after end), generates both cost and benefits; and, resources (human life and other costs) are used to attain the goal. If the war is not winnable or if the expected costs outweigh the benefits, the deciding actors (assuming they are rational) may never go to war (a decision) but rather explore other alternatives. Economics cannot be defined as the science that studies wealth, war, crime, education, and any other field economic analysis can be applied to; but, as the science that studies a particular common aspect of each of those subjects (they all use scarce resources to attain a sought after end).

Some subsequent comments criticized the definition as overly broad in failing to limit its subject matter to analysis of markets. From the 1960s, however, such comments abated as the economic theory of maximizing behaviour and rational-choice modelling expanded the domain of the subject to areas previously treated in other fields.[36] There are other criticisms as well, such as in scarcity not accounting for the macroeconomics of high unemployment.[37]

Gary Becker, a contributor to the expansion of economics into new areas, described the approach he favoured as "combin[ing the] assumptions of maximizing behaviour, stable preferences, and market equilibrium, used relentlessly and unflinchingly."[38] One commentary characterizes the remark as making economics an approach rather than a subject matter but with great specificity as to the "choice process and the type of social interaction that [such] analysis involves." The same source reviews a range of definitions included in principles of economics textbooks and concludes that the lack of agreement need not affect the subject-matter that the texts treat. Among economists more generally, it argues that a particular definition presented may reflect the direction toward which the author believes economics is evolving, or should evolve.[27]

Many economists including nobel prize winners James M. Buchanan and Ronald Coase reject the method-based definition of Robbins and continue to prefer definitions like those of Say, in terms of its subject matter.[36] Ha-Joon Chang has for example argued that the definition of Robbins would make economics very peculiar because all other sciences define themselves in terms of the area of inquiry or object of inquiry rather than the methodology. In the biology department, they do not say that all biology should be studied with DNA analysis. People study living organisms in many different ways, so some people will do DNA analysis, others might do anatomy, and still others might build game theoretic models of animal behavior. But they are all called biology because they all study living organisms. According to Ha Joon Chang, this view that the economy can and should be studied in only one way (for example by studying only rational choices), and going even one step further and basically redefining economics as a theory of everything, is very peculiar.[39]

History of economic thought

This section is missing information about information and behavioural economics, contemporary microeconomics. (September 2020) |

From antiquity through the physiocrats

Questions regarding distribution of resources are found throughout the writings of the Boeotian poet Hesiod and several economic historians have described Hesiod himself as the "first economist".[40] However, the word Oikos, the Greek word from which the word economy derives, was used for issues regarding how to manage a household (which was understood to be the landowner, his family, and his slaves[41]) rather than to refer to some normative societal system of distribution of resources, which is a much more recent phenomenon.[42][43][44] Xenophon, the author of the Oeconomicus, is credited by philologues for being the source of the word economy.[45] Other notable writers from Antiquity through to the Renaissance which wrote on include Aristotle, Chanakya (also known as Kautilya), Qin Shi Huang, Ibn Khaldun, and Thomas Aquinas. Joseph Schumpeter described 16th and 17th century scholastic writers, including Tomás de Mercado, Luis de Molina, and Juan de Lugo, as "coming nearer than any other group to being the 'founders' of scientific economics" as to monetary, interest, and value theory within a natural-law perspective.[46]

Two groups, who later were called "mercantilists" and "physiocrats", more directly influenced the subsequent development of the subject. Both groups were associated with the rise of economic nationalism and modern capitalism in Europe. Mercantilism was an economic doctrine that flourished from the 16th to 18th century in a prolific pamphlet literature, whether of merchants or statesmen. It held that a nation's wealth depended on its accumulation of gold and silver. Nations without access to mines could obtain gold and silver from trade only by selling goods abroad and restricting imports other than of gold and silver. The doctrine called for importing cheap raw materials to be used in manufacturing goods, which could be exported, and for state regulation to impose protective tariffs on foreign manufactured goods and prohibit manufacturing in the colonies.[47]

Physiocrats, a group of 18th-century French thinkers and writers, developed the idea of the economy as a circular flow of income and output. Physiocrats believed that only agricultural production generated a clear surplus over cost, so that agriculture was the basis of all wealth.[48] Thus, they opposed the mercantilist policy of promoting manufacturing and trade at the expense of agriculture, including import tariffs. Physiocrats advocated replacing administratively costly tax collections with a single tax on income of land owners. In reaction against copious mercantilist trade regulations, the physiocrats advocated a policy of laissez-faire, which called for minimal government intervention in the economy.[49]

Adam Smith (1723–1790) was an early economic theorist.[50] Smith was harshly critical of the mercantilists but described the physiocratic system "with all its imperfections" as "perhaps the purest approximation to the truth that has yet been published" on the subject.[51]

Classical political economy

The publication of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations in 1776, has been described as "the effective birth of economics as a separate discipline."[52] The book identified land, labour, and capital as the three factors of production and the major contributors to a nation's wealth, as distinct from the physiocratic idea that only agriculture was productive.

Smith discusses potential benefits of specialization by division of labour, including increased labour productivity and gains from trade, whether between town and country or across countries.[53] His "theorem" that "the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market" has been described as the "core of a theory of the functions of firm and industry" and a "fundamental principle of economic organization."[54] To Smith has also been ascribed "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics" and foundation of resource-allocation theory—that, under competition, resource owners (of labour, land, and capital) seek their most profitable uses, resulting in an equal rate of return for all uses in equilibrium (adjusted for apparent differences arising from such factors as training and unemployment).[55]

In an argument that includes "one of the most famous passages in all economics,"[56] Smith represents every individual as trying to employ any capital they might command for their own advantage, not that of the society,[a] and for the sake of profit, which is necessary at some level for employing capital in domestic industry, and positively related to the value of produce.[58] In this:

The Rev. Thomas Robert Malthus (1798) used the concept of diminishing returns to explain low living standards. Human population, he argued, tended to increase geometrically, outstripping the production of food, which increased arithmetically. The force of a rapidly growing population against a limited amount of land meant diminishing returns to labour. The result, he claimed, was chronically low wages, which prevented the standard of living for most of the population from rising above the subsistence level.[60][non-primary source needed] Economist Julian Lincoln Simon has criticized Malthus's conclusions.[61]

While Adam Smith emphasized production and income, David Ricardo (1817) focused on the distribution of income among landowners, workers, and capitalists. Ricardo saw an inherent conflict between landowners on the one hand and labour and capital on the other. He posited that the growth of population and capital, pressing against a fixed supply of land, pushes up rents and holds down wages and profits. Ricardo was also the first to state and prove the principle of comparative advantage, according to which each country should specialize in producing and exporting goods in that it has a lower relative cost of production, rather relying only on its own production.[62] It has been termed a "fundamental analytical explanation" for gains from trade.[63]

Coming at the end of the classical tradition, John Stuart Mill (1848) parted company with the earlier classical economists on the inevitability of the distribution of income produced by the market system. Mill pointed to a distinct difference between the market's two roles: allocation of resources and distribution of income. The market might be efficient in allocating resources but not in distributing income, he wrote, making it necessary for society to intervene.[64]

Value theory was important in classical theory. Smith wrote that the "real price of every thing ... is the toil and trouble of acquiring it". Smith maintained that, with rent and profit, other costs besides wages also enter the price of a commodity.[65] Other classical economists presented variations on Smith, termed the 'labour theory of value'. Classical economics focused on the tendency of any market economy to settle in a final stationary state made up of a constant stock of physical wealth (capital) and a constant population size.

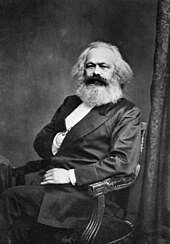

Marxian economics

Marxist (later, Marxian) economics descends from classical economics and it derives from the work of Karl Marx. The first volume of Marx's major work, Das Kapital, was published in German in 1867. In it, Marx focused on the labour theory of value and the theory of surplus value which, he believed, explained the exploitation of labour by capital.[66] The labour theory of value held that the value of an exchanged commodity was determined by the labour that went into its production and the theory of surplus value demonstrated how the workers only got paid a proportion of the value their work had created.[67][dubious ]

Marxian economics was further developed by Karl Kautsky (1854–1938)'s The Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx and The Class Struggle (Erfurt Program), Rudolf Hilferding's (1877–1941) Finance Capital, Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924)'s The Development of Capitalism in Russia and Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, and Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919)'s The Accumulation of Capital.

Neoclassical economics

At its inception as a social science, economics was defined and discussed at length as the study of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth by Jean-Baptiste Say in his Treatise on Political Economy or, The Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth (1803). These three items were considered only in relation to the increase or diminution of wealth, and not in reference to their processes of execution.[b] Say's definition has survived in part up to the present, modified by substituting the word "wealth" for "goods and services" meaning that wealth may include non-material objects as well. One hundred and thirty years later, Lionel Robbins noticed that this definition no longer sufficed,[c] because many economists were making theoretical and philosophical inroads in other areas of human activity. In his Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, he proposed a definition of economics as a study of human behaviour, subject to and constrained by scarcity,[d] which forces people to choose, allocate scarce resources to competing ends, and economize (seeking the greatest welfare while avoiding the wasting of scarce resources). According to Robbins: "Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses".[34] Robbins' definition eventually became widely accepted by mainstream economists, and found its way into current textbooks.[68] Although far from unanimous, most mainstream economists would accept some version of Robbins' definition, even though many have raised serious objections to the scope and method of economics, emanating from that definition.[69]

A body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularized by such neoclassical economists as Alfred Marshall and Mary Paley Marshall as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier "political economy".[24][25] This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the natural sciences.[70]

Neoclassical economics systematized supply and demand as joint determinants of price and quantity in market equilibrium, affecting both the allocation of output and the distribution of income. It dispensed with the labour theory of value inherited from classical economics in favour of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and a more general theory of costs on the supply side.[71] In the 20th century, neoclassical theorists moved away from an earlier notion suggesting that total utility for a society could be measured in favour of ordinal utility, which hypothesizes merely behaviour-based relations across persons.[72][73]

In microeconomics, neoclassical economics represents incentives and costs as playing a pervasive role in shaping decision making. An immediate example of this is the consumer theory of individual demand, which isolates how prices (as costs) and income affect quantity demanded.[72] In macroeconomics it is reflected in an early and lasting neoclassical synthesis with Keynesian macroeconomics.[74][72]

Neoclassical economics is occasionally referred as orthodox economics whether by its critics or sympathizers. Modern mainstream economics builds on neoclassical economics but with many refinements that either supplement or generalize earlier analysis, such as econometrics, game theory, analysis of market failure and imperfect competition, and the neoclassical model of economic growth for analysing long-run variables affecting national income.

Neoclassical economics studies the behaviour of individuals, households, and organizations (called economic actors, players, or agents), when they manage or use scarce resources, which have alternative uses, to achieve desired ends. Agents are assumed to act rationally, have multiple desirable ends in sight, limited resources to obtain these ends, a set of stable preferences, a definite overall guiding objective, and the capability of making a choice. There exists an economic problem, subject to study by economic science, when a decision (choice) is made by one or more players to attain the best

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen